The entire "A USDA Regional Roadmap to Meeting the Biofuels Goals of the Renewable Fuels Standard by 2022 - USDA Biofuels Strategic Production Report" is included and attached below:

A USDA Regional Roadmap to Meeting the Biofuels Goals of the Renewable Fuels Standard by 2022

USDA Biofuels Strategic Production Report - June 23, 2010

I. INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is developing a comprehensive regional strategy to

help recharge the rural American economy. The strategy targets barriers to the development of a

successful biofuels market that will achieve, or surpass, the current U.S. Renewable Fuels

Standards (RFS2), as set out in the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA). The

RFS2, implementation provisions of which are detailed in the Environmental Protection

Agency’s RFS2 Final Rule (March 26, 2010 Federal Register), becomes effective on July 1,

2010. The RFS2 will create new market opportunities for American agriculture to help fulfill its

mandate: the American economy will be using 36 billion gallons (bg) of renewable

transportation fuel per year in its transportation fuel supply by 2022.

USDA is uniquely positioned, given its detailed knowledge of the agriculture sector, to

understand and support the goals of RFS2 at an agricultural regional level. When President

Obama established a Biofuels Interagency Working Group (BIWG) it was intended to coordinate

the federal government’s efforts on the nation’s first comprehensive biofuel market development

program. The BIWG is using existing authorities and new policies to support the development

of next-generation biofuels, increase flexible fuel vehicle use, and assist in retail marketing

efforts. The Working Group is co-chaired by the Secretaries of Agriculture and Energy and the

Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. The BIWG brings together and engages

in inter-agency policy discussions on the growing biofuels industry.

As part of that larger conversation, USDA’s objectives for this report include: providing the

practical knowledge from the field that can enhance various models for biofuel production,

identify challenges and opportunities, and help develop solutions to this massive undertaking. In

addition, USDA hopes that this report spurs discussions and is looking forward to feedback from

Congress, states, industry, science, and all concerned citizens and stakeholders.

This report is the work of multiple agencies at USDA, including Rural Development, the Natural

Resources Conservation Service, the Forest Service, and the Farm Services Agency, as well as

the Office of the Chief Economist and its Office Energy Policy and New Uses, among others, to

assess: existing eligible feedstock supply and land availability, current and potential

infrastructure capacity, and current and potential regional consumer demand. The report relies on

the work of other agencies as inputs, though the analytical approach was developed by USDA.

This is an interim product subject to revision given more inputs, including the work of the

Biofuels Interagency Working Group.

Over the last 60 years, the percentage of the U.S. population directly involved in production

agriculture in America has gone from 15 percent to less than two percent, but the average farmer

produces food for 155 people today, as compared to his counterpart 60 years ago who produced

food for only 25 people. This increase in efficiency in agriculture and farming, and the resulting

sharp decrease in the number of hands needed to meet a growing demand, by its very nature,

requires that the rural economy diversify. Growing a domestic biofuels market is part of overall

USDA rural strategy to help rebuild rural America.

II. WE ARE ALREADY ON OUR WAY: The Role of Corn Starch Ethanol

The Congressionally mandated RFS2 goal is to use at least 36 billion gallons of bio-based

transportation fuels by 2022 that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the percentages specified

under the RFS2. Fifteen billion gallons can come from conventional biofuel sources such as

corn ethanol. EPA’s analysis projects that 15 billion gallons of conventional biofuels could

come from current or planned production capacity of corn starch ethanol by 2022.

In 2009, the United States produced 10.75 billion gallons of ethanol, primarily as corn starch

ethanol. The expectation for 2010 is for the United States will produce approximately 12.0

billion gallons of ethanol. According to the Renewable Fuel Association (RFA), there are

currently 201 ethanol facilities with a capacity to produce 13.5 billion gallons (RFA, April 27,

2010). In addition, there are facilities currently under construction that will add another 1.2 bg

of capacity of corn starch ethanol. As a result, the United States will soon have the installed

capacity to produce up to the 15.0 billion gallons of corn-starch ethanol that is allowed by RFS2.

This means that we are already well on our way to meeting the 36 billion gallon goal. See

Appendix A for a state by state breakdown of the current state of ethanol production in the

United States.

III. MEETING THE 21 BILLION GALLON ADVANCED BIOFUELS CHALLENGE

Of the remaining 21 billion gallons of advanced biofuels needed to achieve the total 36 billion

gallon goal, 16 billion gallons is required to come from advanced cellulosic biofuels (fuels made

from cellulosic feedstocks that also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 60 percent

relative to gasoline). The contribution of biomass-based diesel to the 21 billion gallons goal can

be no less than 1 billion gallons and will be determined at a later date by rulemaking. An

additional 4 billion gallons of advanced biofuels (defined by the reduction of greenhouse gas

emissions by at least 50 percent) by 2022 is also mandated by EISA.

Biodiesel One Billion.

The U.S biofuels industry is on track to produce 1 billion gallons of

biodiesel by 2022. In 2009, the United States already produced 550 million gallons of biodiesel.

There are presently 173 plants and nearly as many companies that have invested millions of dollars into

the development of biodiesel manufacturing plants and are actively marketing biodiesel. Twenty-nine

companies have reported that they have plants currently under construction and are scheduled to

be completed within the next 12-18 months. Their combined capacity, if realized, would result in

another 427.8 million gallons per year of biodiesel production.

The remaining 20-bg challenge: cellulosic and other advanced biofuels. USDA is working

to establish a sustainable biofuels economy to help meet the 20-billion gallons of advanced

biofuels challenge. The intention is to develop strategic partnerships with the private sector. By

so doing, we expect to expedite the development and deployment of research, development and

demonstration projects, facilitate the siting of biorefineries through loan guarantees and other

existing programs, and identify potential barriers to meeting transportation and distribution needs

for an advanced biofuels industry. The analysis presented below presents one scenario by which

the RFS targets could be met. It is based on a USDA analysis of regional feedstock availability

and other factors. This analysis is based on converting agricultural and forestry feedstocks to

ethanol; however, these feedstocks could be converted to other potential fuels such as methanol

biobutanol, green gasoline, and jet fuel (i.e. JP-8.)

(A) Feedstock Assumptions and Limitations

USDA has developed feedstock production scenarios based on dedicated crop feedstocks and

waste wood biomass that come from timberland and agricultural lands that are a subset of the

RFS2 definitions and assumptions. What is encouraging is that USDA considers these estimates

as conservative, because the estimates do not include all possible feedstock sources that may

eventually be eligible to achieve the 21 billion gallons of advanced biofuels as specified by

RFS2. This is good news since qualified feedstocks identified by EPA but not included in the

current USDA analysis (e.g., tallow, municipal solid waste) could be counted toward meeting the

RFS2 mandate. In addition, if technologies are developed in a timely manner to use an even

wider variety of feedstocks, increase conversion ratios, or utilize waste or co-products

technologies, while meeting greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, then the total volume of

biofuels from approved feedstocks produced that meet emissions specified may exceed the 36

billion gallon RFS2 targets.

Feedstock Choice.In the RFS2 Final Rule, the EPA identifies a number of feedstock pathways

and imports that would satisfy the RFS2 mandates. Feedstock pathways for advanced biofuels

include switchgrass, soybean oil, corn oil, crop residues, woody biomass and other feedstocks.

The complement of feedstocks included in this USDA analysis and those identified by the EPA

should not be considered an exhaustive list of all possible feedstock sources. The petition

process exists to embrace the possibilities of technological advances and research evolution. In

order to be successful in the implementation of a domestic biofuels industry this flexibility

should be utilized in considering all the feedstock resources that America has to offer that meet

the greenhouse gas requirements and other restrictions of the RFS2.

USDA scientists, intramural and extra-mural research, and collaborative work with other Federal

agencies (i.e. Navy, Air Force) suggest that additional feedstocks such as biomass (sweet)

sorghum, energy cane, and camelina may merit consideration under the RFS2. For the purposes

of this analysis, USDA assumed that these feedstocks were sufficiently similar to those already

eligible under the Renewable Fuels Standard and necessary to the regional approach. USDA

recognizes that a formal review by the EPA of each of the feedstocks would be required to

evaluate whether they qualify as an advanced biofuel.

Feedstock Definitions.

EISA includes specific greenhouse gas reduction thresholds levels for

renewable fuel mandates that feedstock pathways must meet. The EPA in its analysis of the

feedstock pathways was required to carry out a complete greenhouse gases life-cycle-analysis,

which considers reductions in carbon emissions and other greenhouse gas. In addition, EISA

provides a specific definition of renewable biomass and places constraints on the types of land

from which renewable biomass can be collected or harvested. For the sake of consistency USDA

chose to use those definitions in the context of this report.

Feedstock Assumption Summary

EPA expects the following feedstocks and the associated number of gallons by 2022:

Switchgrass (perennial grass): 7.9 bg

Soy biodiesel and corn oil: 1.34 bg

Crop residues (corn stover, includes bagasse): 5.5 bg

Woody biomass (forestry residue): 0.1 bg

(data does not include short-term woody crops)

Corn ethanol: 15.0 bg

Other (municipal solid waste (MSW)): 2.6 bg

Animal fats and yellow grease: 0.38 bg

Algae: 0.1 bg

Imports: 2.2 bg

USDA estimates the following feedstocks and the associated gallons by 2022: (this count

does not include tallow, MSW, or algae)

Dedicated energy crops:

perennial grasses, energy cane, biomass sorghum: 13.4 bg

Oilseeds (soy, canola): 0.5 bg

Crop residues (corn stover, straw): 4.3 bg

Woody biomass (logging residues only): 2.8 bg

Corn starch ethanol: 15.0 bg

1Biofuels that have a higher energy density than ethanol receive a greater weighting as it contributes to the RFS2

mandate total. For example, each gallon of biodiesel counts as 1.5 gallons of renewable toward the mandate. On

a volume basis, the total for those feedstock pathways will sum to less than 36 bg.

2 These calculations are based on research by Agricultural Research Service scientists who calculated energy yield

by feedstock. In addition, the feedstocks used for this report are those USDA posits are most likely to be produced

in volume.

3 This calculation is based on the sum of the energy yields per acre of the analyzed feedstocks.

(B) Land Use Assumptions and Limitations

Consistent with EISA, USDA assumes that biomass may be grown on defined agriculture

cropland (agriculture cropland where crops are produced and agriculture cropland in pasture). To

produce this much in biofuels will take 27 million acres of cropland,3 6.5 percent of the total

406.4 million acres of cropland as reported in the 2007 Census of Agriculture (COA). This does

not include acreage of timberland harvested from which logging residues are viable feedstocks,

nor does it include acreage from traditional food crops from which post harvest crop residues are

collected. Importantly, USDA will assess the acreage of fallow and underutilized lands that can

be sustainably converted into dedicated energy crops.

Cropland.

The UDSA’s 2007 COA reports that there is a total of 922.1 million acres of Land in

Farms. The category land in farms is comprehensive and represents all land in farms: land that is

defined as agriculture cropland (406.4 million acres) and other land (515.7 million acres).

Cropland is further segmented into the following categories: cropland harvested, cropland used

as pasture (land that could be planted, but is in pasture the year of the COA), other crop land that

is idled for conservation or intentional purposes, summer fallow, and failed crops. Cropland

harvested is the larger category accounting for 76 percent of the total cropland.

Land in Farms (1,000 Acres) 2007

Total land in farm 922,095

Total cropland 406,424

Cropland harvested 309,607

Other land 515,671

Cropland in Agriculture (1,000 Acres) 2007

Cropland harvested 309,607

Cropland used for pasture 35,771

Cropland cover crop not harvested pasture 37,969

Summer fallow 15,671

Cropland on which all crops faile 7,405

Cropland idle 0

Total 406,423

EISA provides a definition of renewable biomass that is more restrictive than the Farm Bill

definition of renewable biomass. EISA restricts where feedstocks can grow and be harvested for

use in producing renewable fuels for compliance with the RFS2. For planted crops/crop residue

from agricultural land and planted trees/tree residue from actively managed tree plantations on

non-federal land, feedstocks must come from land cleared/cultivated land prior to December 19,

2007. EPA’s approach excludes rangeland as an approved land type from which renewable

biomass could be produced or harvested.

Forested land.

USDA estimates of biomass from logging residues are based on actual data from

the 2001 – 2005 period. The average annual volume of logging residues (all species), average

over the 2001-2005 period, is assumed available per annum. The total and harvested timberland

area is also averaged over 2000-2005 period to give an estimate of the area that logging residues

actually come from and, potentially, how large or how much biomass might be available. For

the purposes of this analysis 42.5 million dry tons of logging residues, used for no other purpose

and totaling only a percentage of the total logging residues actually generated by logging

practices, is available for fuel production annually. This residue is taken from 10.8 million acres

of harvested acreage, as compared to the 507.3 million acres of timberland available for

harvesting activities. One dry ton of logging residues is assumed to yield 70 gallons of ethanol

per dry ton. In total, about 2.8 billion gallons of advanced biofuels is projected from logging

residues when the conversion technology is commercialized.

(C) USDA Regional Analysis Assumption Summary

USDA recognized that different regions of the country have a comparative advantage to the type

of feedstocks that can be produced and utilized in biofuel production. By leveraging the

availability of these regional resources, diversification of biofuel production will be a national

solution to reducing the Nation’s dependence on oil, much of which is imported.

These regions were determined based upon the prevalence of potential crop and woody biomass

feedstocks adapted to different ecological regions of the county, their yields, and current

producer interest. USDA estimated 4 the following regional biofuel contributions to the RFS2

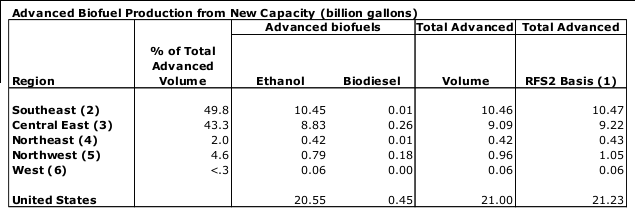

advanced biofuel goal of at least 21 billion gallons a year by 2022:

Southeast: 49.8%

Northeast : 2.0%

Central-Eastern: 43.3%

Northwest: 4.6%

Western: < 0.3%,

assumed 0 for crop biomass, though there is opportunity for algae and woody biomass

(1) RFS2 basis - higher density fuels receive higher weighting relative to ethanol. Biodiesel weight is 1.5

(2) Feedstocks: Perennial grasses, soyoil, energy cane, biomass (sweet) sorghum, logging residues

(3) Feedstocks: Perennial grasses, canola, soyoil, biomass (sweet) sorghum, corn stover, logging residues

(4) Feedstocks: Perennial grasses, soyoil, biomass (sweet) sorghum, corn stover, logging residues

(5) Feedstocks: C anola,straw, logging residues

(6) Feedstocks: Biomass (sweet) sorghum, logging residues

4 These estimates are based on energy yield per acre per feedstock, and estimates of acreage planted to those

feedstocks as regionally appropriate.

IV. OVERCOMING INFRASTRUCTURE BARRIERS TO CONVERTING BIOMASS INTO BIOFUELS

(A) Introduction.

This section of the report lays out the availability and regional distribution of the resources

needed to produce the biofuels to reach the RFS2 target of 36 bg of renewable biofuels per year.

In addition, it presents a path to the regional diversification of advanced biofuels, benefiting

multiple local communities across the country. This information should assist the government in

pinpointing potential barriers and bottlenecks to investment and assist the industry in developing

commercially viable enterprises that will benefit both the rural economy and U.S. consumers.

Assuming an average biorefinery size of 40 million gallons per year, USDA estimates it meeting

the RFS2 advanced biofuels goals will mean building of 527 biorefineries, at a cost of $168

billion.5 While we expect the market to react to this need, biorefineries will need to be

constructed in a timely manner, while accounting for transportation needs for feedstocks and fuel

distribution.

(B) Regional Status and Outlook on Advanced Biofuels Production

Review of Assumptions.

Costs.

USDA assumed a steady cellulosic plant construction cost of $8 per gallon.

We recognize that initial construction costs for first of a kind plant will typically be

greater than the costs of plants that follow; however, we assume a fixed capital cost

over time. Plant construction costs decline in real terms for this analysis.

Size.

This approach assumes each biorefinery built will have a capacity of 40 million

gallons a year.

Biofuel Regions.

Based on work by the Agricultural Research Service, biofuel

feedstock regions were developed based on crops that we expect will be prevalent in

those areas based on historic planting data and weather, soil and water conditions.

Energy Yields per Acre.

Through ARS research, we could assume certain energy

yields per acre by feedstock and thereby estimate the number of biorefineries

necessary for each region to fill their expected biofuels goals.

Technology Changes.

For the sake of this report, we assume no technology change,

which make our estimates conservative. This is a very conservative assumption as

RFS2 is predicated on challenging the industry to create newer, cleaner fuels. Also,

the agricultural sector as a whole is incredibly productive and has consistently

outpaced productivity increases in other sectors, in part, due to its investment in

technology (e.g. drought resistant seeds).

5 This figure comes from the analysis of USDA received applications for funding biorefineries that average the cost

of building the biorefinery divided by the projected plant capacity.

1. SOUTHEAST REGION and HAWAII:

States. Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North

Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas

Feedstocks. Soybean oil, Energy cane, Biomass Sorghum, Perennial grasses, Woody biomass

Other Points of Interest. Hawaii, Florida, Georgia and Texas are the largest consumers of

petroleum in the region. USDA has an MOU to provide biofuels to the Navy in Hawaii that

involves research and development as well as implementation. With the Western Naval fleet in

HI, there is already a consumption base from the Navy of 80 million gallons of fuel a year.

Current Production Capacity.

Ethanol Biorefineries: Total facilities 20—17 producing, 2 idle, and one in construction

GA—2 producing; 1 in construction

KY—3 producing

LA—1 producing

MS—1 producing

NC—5 producing; 2 idle

TN—2 producing

TX—3 producing

Biodiesel Refineries: Total facilities 67—40 producing; 25 idle; 1 unknown status; 1 in

construction

AL—3 producing; 3 idle

AR—2 producing

FL—1 producing; 2 idle; 1 unknown status

GA—6 producing; 1 idle

HI—1 producing; 1 idle

KY—3 producing; 1 idle

LA—0 producing; 1 idle

MS—5 producing

NC—1 in construction

SC—3 producing

TN—3 producing; 3 idle

TX—13 producing; 10 idle

Potential Production Capacity.

This region could produce 10.5 billion gallons of advanced

biofuels per year, at 263 biorefineries producing 40 million gallons by year, costing $320 million

per biorefinery. This will take an $83.8 billion cumulative investment, to build the 263

biorefineries with an average capacity of 40 million gallons. USDA estimated that a significant

amount of volume, up to 50%, of the advanced biofuels, could come from this region because it

has the most robust growing season in the United States that supports the highest gallons-per-

acre crops of all biofuels crops. One advanced fuel biorefinery is expected to open in August of

2010 in Louisiana, with expected production of 75 million gallons.

Land Use.

In this region there is an acreage base of 83.4 million acres of cropland and cropland

pasture and 182.8 million acres of forest land. To produce the biofuels necessary from this

region, an advanced biofuel production of 10.5 billion gallons from 9.5 million acres, 11.4% of

the available cropland and cropland pasture acreage base, would be required for fuel use.

2. NORTHEAST REGION

States. Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York,

Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia

Feedstock. Woody biomass, municipal waste potential

Other Points of Interest. In addition to woody biomass there is corn in NY, and other row

crops in Southern PA which we have not taken into account yet. Other sources and affects yet to

be considered are municipal solid waste availability and existing infrastructure, brownfields, that

may be suitable sites for biorefineries.

Current Production Capacity.

Ethanol Biorefineries: Total 7 facilities producing

MI—5 producing

NY—2 producing

Biodiesel Refineries: Total 20 potential facilities—9 producing, 2 in construction; 5 with

unknown production status; 4 idle

CT—1 unknown status

MA—1 unknown status

ME—2 producing

MI—2 producing

NH—1 in construction; 1 unknown status

NJ—2 producing; 1 unknown status;

NY—3 producing; 1 in construction; 1 idle

RI—1 producing; 1 unknown status

WV—1 producing

Potential Production Capacity.

USDA estimates that 2.0% of advanced biofuel production

(mostly woody biomass) will come from the Northeast. The region could produce 423.7 million

gallons of advanced biofuels from 639,150 acres of dedicated bioenergy crops (perennial

grasses) plus 1.7 million acres of harvested logging residue in a year. This will take 11

biorefineries, producing 40 million gallons by year, costing $320 million per biorefinery, for a

total cost of $3.52 billion cumulative investment over time.

Land Use.

In the Northeast there is an acreage base of 15.1 million acres of cropland and

cropland pasture and 79.3 million acres of timber land. Approximately 4.5% of the available

cropland and cropland pasture acreage base is used in meeting the advanced biofuel mandates.

3. CENTRAL EAST REGION

States. Delaware, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, Maryland,

Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Virginia.

Feedstock.

Perennial grasses, biomass sorghum, crop residues, soy beans, woody biomass.

Other Points of Interest.

The Central East Region of the United States is one of two regions

with the most potential for near and long term development of biofuels. Based on feedstock and

land, infrastructure, and demand this region is key in implementing a successful biofuels market.

The current cap in the RFS2 as a result of EISA is 15 billion gallons of corn-starch ethanol. This

region will produce the last 4.25 billion gallons to reach the cap.

Current Production Capacity.

12 billion gallons per year conventional ethanol, .5 billion

gallons per year of biodiesel

Ethanol Biorefineries: Total facilities 171—170 facilities producing, one in construction

IA—40 producing

IL—13 producing

IN—11 producing

KS—12 producing; 1 in construction

MN—27 producing

MO—5 producing

ND—6 producing

NE—22 producing

OH—8 producing

PA—1 producing

SD—15 producing

VA—1 producing

WI—9 producing

Biodiesel Facilities: Total facilities 84 facilities—5 unknown, 14 idle, 63 producing; 2 in

construction

DE—1 idle

IA—8 producing; 6 idle

IL—4 producing; 3 idle; 1 in construction

IN—6 producing; 1 in construction, 1 unknown status

KS—1 producing

MD—5 producing; 1 unknown status

MN—3 producing; 2 unknown status

MO—11 producing

OH—8 producing; 3 idle

OK—2 producing; 1 idle

PA—7 producing

SD—1 producing

VA—3 producing

WI—3 producing; 1 unknown status

Potential Production Capacity.

USDA estimates that on a volume basis, 43.3% of the 20

billion gallons of advanced biofuel by 2022 will be produced in the Central East region. This

will take $72 billion in cumulative investments to build 226 biorefineries with an estimated

capacity of 40 million gallons per year.

Land Use.

This region has an acreage base of 241 million of cropland and cropland pasture plus

109.8 million acres of timber land that could produce 9.1 billion gallons from 10.8 million acres

of dedicated bioenergy crops plus 2.0 million acres of harvested logging residue in a year

Incremental advanced biofuel production will take up 4.5% of the available cropland and

cropland pasture acreage base.

4. NORTHWEST REGION

States. Alaska, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington

Feedstock. Woody biomass, oil seed, grasses, cereal crop residue.

Other Points of Interest.

We have 100 million gallons a year currently being produced in this

region from canola, but much of the feedstock is imported from Canada and at this time canola is

not an approved feedstock pathway under the RFS2.

Current Production Capacity.

Ethanol Biorefineries: Total 4 facilities producing

ID—2 producing

WA—2 producing

Biodiesel Facilities: Total 10 facilities—7 producing, 1 idle, 2 in construction

ID—2 producing; 1 in construction

OR—1 producing

WA—4 producing; 1 idle; 1 in construction

Potential Production Capacity.

USDA estimates that 4.6% of advanced biofuel production of

the 21 billion gallons required by 2022 (primarily oilseed crops) will be from the Northwest

region. This will take an $8.32 billion investment to build 27 biorefineries with an average

capacity of 40 million gallons per year.

Land Use.

Acreage base of 36.9 million acres of cropland and cropland pasture plus 86.4 million

acres of forest land. To produce the 1 billion gallons from 2.5 million acres of dedicated

bioenergy crops plus 911,500 acres of harvested logging residue in a year it will take 6.9% of the

available cropland and cropland pasture acreage base.

5. WESTERN REGION

States. Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming

Feedstock. Woody biomass, Oilseed crops (e.g. camelina, canola); potential for algae not

included.

Other Points of Interest.

While this region has potential for development of biofuels, it is very

limited and the total contribution to meeting the RFS2 requirement is less than 1%. That said,

USDA has already funded one commercial scale algae based biorefinery in New Mexico and

expects to see more efforts on algae based biofuels in California, among other places. As this

technology develops for algae, the US will have another feedstock resource contributing to

RFS2.

Current Production Capacity.

Ethanol Biorefineries: Total 15 facilities—13 producing, 2 in construction

AZ—1 producing

CA—6 producing; 1 in construction

CO—4 producing; 1 in construction

NV—1 producing

WY—1 producing

Biodiesel Facilities: Total 27 facilities—18 producing, 5 idle, 3 in construction, 1

unknown

AZ—3 producing

CA—13 producing; 3 idle; 2 in construction

CO—2 producing; 1 idle

NM—1 idle; 1 unknown status

NV—1 in construction

Potential Production Capacity.

USDA assumes 0.3% of the 21 billion gallons of advanced

biofuel by 2022 (this is only for dedicated energy crops and woody biomass from logging waste).

Commercial scale algae production is not included.

Land Use.

In this region there is an acreage base of 29.7 million of cropland and cropland

pasture plus 48.9 million acres of forest land. While 64 million gallons from 49,800 acres of

dedicated bioenergy crops plus 442,600 acres of harvested logging residue in a year (does not

include potential from insect and disease damaged and dead trees that could be harvested) is a

potential, it is not counted as part of the RFS2.

V. INFRASTRUCTURE CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE EXPANDED USE OF BIOFUELS

There are a number of potential barriers and bottlenecks in the current ethanol use supply chain.

While we expect the market to respond to the infrastructure needs of a growing industry, we

recognize that the path from production to actual consumption presents challenges that will need

to be anticipated and addressed. For example, the vehicle fleet in the United States today

currently is not able to accept ethanol blends higher than 10% due to the technical challenge of

overcoming the ―blend wall‖.6 EPA is in the process of evaluating whether a decision to blend

up to 15 percent ethanol into gasoline is justifiable based on the latest science, its effect on

engines, and its effect on air quality. In addition, the only other fuel currently utilized by

vehicles on the road today is E85, which can be utilized in a flex-fuel vehicle (FFV). The limited

number of FFVs, their relatively low utilization of bio-based fuels instead of gasoline, and the

inability of the rest of the vehicle fleet to utilize higher blends, restricts the amount of ethanol

that can actually be consumed.

In conjunction with meeting the blend wall and FFV challenges, there is a need to evaluate

infrastructure needs to both distribute (rail and truck, blending terminals and storage) and

dispense fuel (blender pumps, refueling stations). These issues can affect decisions in siting

biorefineries, in addition to many other components such as feedstock availability, land and

water availability. Key among them are distribution concerns. For instance, biorefineries with

production capacity below 100 million gallons per year will likely depend on truck service to

deliver the feedstocks to the biorefinery and the fuel to market (petroleum blending terminal or

retail stations). However, if enough biorefineries are located in close proximity to each other,

rail service may be a viable option. For retail sales, the installation of blender pumps will be

necessary at the retail level to provide outlet of the product to the consumer.

We provide an assessment of current capacity including the availability of blender pumps and

transportation infrastructure.

Blender Pumps.

While the market will determine the ultimate need for blender pumps, this is

one area that USDA can immediately offer assistance on infrastructure, beyond the work USDA

Rural Development is already doing on biorefinery construction and upgrade loans and grants.

The number of FFV vehicles in service and locations of concentrations of these vehicles is a

good indicator of current blender pump needs. The number of Flex Fuel Vehicles (FFVs)

currently on the road is between 8.0 and 8.5 million. They constitute about 3.2 – 3.5 percent of

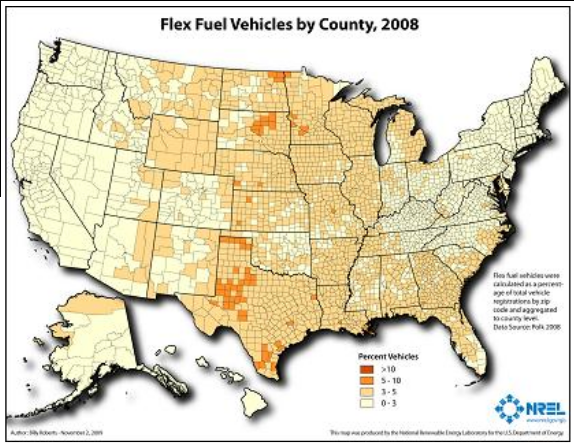

the approximately 250 million vehicles on the road. The map below shows the distribution of

FFVs by county (NREL), indicating the concentration of FFVs is mainly near the ethanol-

producing region.

6 Growth Energy has submitted a waiver request to EPA to allow E15. Archer Daniels Midland has requested EPA,

on the basis of substantially similar rationale, that E11/E12 be approved.

The bulk of the FFVs are located in the Midwest. However, see figure below, there is a demand

for ethanol outside the Midwest. Approximately 40 counties in Texas, 2 in Kansas, 3 in

Nebraska, 8 in South Dakota, 3 in North Dakota, 6 in Minnesota, and 1 in Missouri have a

concentration of FFVs in the 5 – 10 percent range. On a land density basis (FFV/5 sq. miles), the

FFVs are concentrated in the East and West Cornbelt and the Southern and Northern Plains

states. In the West Coast markets such as, California, Arizona, Washington, and Oregon and in

the Northeast states, however, there is an opportunity to increase the number of FFVs because

currently their share in those major markets is low.

The top five states in terms of FFVs are Texas, Florida, California, Michigan and Ohio and they

account for one-third of the FFVs (July 1, 2009). One point of information—due to the total

number of vehicles in the urban areas of California and Michigan—they are boosted into the top

five states in terms of FFVs.

The map below shows that California, Texas and Florida are the States with the highest

consumption of ethanol and may be the primary targets for blender pumps and flex-fuel vehicles.

According to the EPA, CFDC, RFA and NREL there is a wide range in the estimated cost to

install blender pumps. The range in costs is directly attributed to whether existing pumps can be

modified or need to be replaced and whether Underground Storage Tanks (UST) need to be put

in or modified. If a station is currently selling E85, for instance, the pump could be modified so it

could pump fuel from the E85 tank and an E10 tank to deliver an alternative blend.

The cost for a standard fuel dispenser is $14,000 (American Coalition for Ethanol - Lamberty)

and for an E85 dispenser $23,000. The cost of a blending pump would more closely match that

of an E85 pump. Each pump has two fueling positions. The EPA (RIA) estimates that if the

hoses on a dispenser needed to be replaced this could be done for $750 plus a $25 installation fee

(total cost of $775 per dispenser). If the wetted fuel dispenser components needed to be replaced,

this could be done for $10,000 (components) and an installation fee of $1,000. The total cost to

modify the standard pump would include hoses, wetted components and installation for an

estimated cost of $11,775.

EPA estimates that the average cost to install a new tank and above ground E85 dispensing

equipment is $122,000 per retail station. Fueling facilities can install an E85 pump and net out

the cost with the tax credit for infrastructure, but, it is only for the E85 portion of the pump. The

tax credit was originally 30 percent or $30,000 of the cost of infrastructure (tanks, pumps, etc.);

in 2009 was increased to 50 percent or $50,000. This tax credit is set to expire at the end of

2010.

If facilities need to break cement or ground to modify pipes, tanks or add tanks, EPA estimates

the cost to average $25,000 – facilities that require more extensive UST modification would cost

more, while those requiring less work would cost less. Assuming the blender pump costs are

similar to E85 and the potential underground work, the cost could rise to more than $50,000 for

one blender pump installation. Multiple pump installations at one facility would spread the

underground work cost across more pumps. An NREL 2008 survey of 120 stations found that

the median cost to add a new tank was $59,000.

These figures indicate that the cost to install blender pumps can vary widely which means that

the support necessary for this process must be flexible. In addition to federal support, some

states provide support to offset some of the installation costs to the fueling stations in installing

blender pumps. Growth Energy began a program recently that offers up to $5,000 to help defray

the costs of procurement and installation.

A number of states have incentives designed to stimulate consumption of biofuels. A state by

state listing is not possible at this time, but USDA is in the process of compiling one, with the

help of the states. The incentives could include: industry recruitment incentives, corporate tax

credits, net metering policies, grants, loan programs, rebate programs, personal tax credits, sales

tax exemptions, property tax exemptions, and production incentives. However, more than half of

the states provide some E85 production and/or sale encouragement.

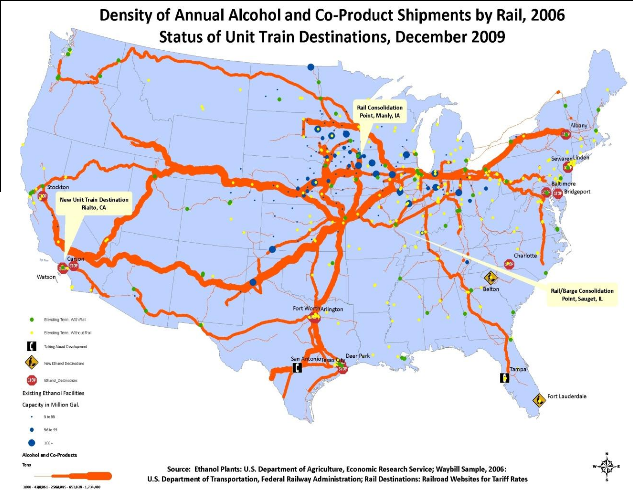

Rail and Trucking Infrastructure.

Current conditions for ethanol distribution should guide us

in evaluating potential gaps in infrastructure needs as biofuels supply increases and demand

responds as it becomes more widely available and competitive with other fuels. Ethanol

consumption has followed a gradual regional development. Most of ethanol is distributed by

rail, but only about 15 percent of petroleum blending terminals that handle ethanol have rail

access—most are serviced by pipelines for petroleum products and trucks for ethanol. The map

below shows the current patterns of ethanol distribution.7 It shows the concentration of rail

corridors from the producing area in the Midwest to the consumption areas along the coasts. It

also identifies the location of all ethanol blending terminals.

7 For a more in-depth look at biofuel transportation, please see Chapter 4 of the USDA/DOT Study of Rural

Transportation Issues: http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/RuralTransportationStudy

Based on a model developed by Oakridge National Laboratories, EPA projects that 40 unit train

rail receipt facilities will be needed to distribute additional volumes of ethanol as targeted by the

RFS2. Additional unit-train destinations would likely create more ethanol corridors on the rail

network, possibly alleviating congestion points that could develop with increased biofuel

shipments. In addition to unit trains, EPA expects manifest rail cars (shipments of less than 80–

100 railcar unit trains) will continue to be used to ship ethanol and cellulosic biofuels. EPA

estimates the capital costs for the ethanol distribution infrastructure would total $12.066 billion.

When amortized, this translates to 6.9 cents per gallon of additional costs associated with

shipping RFS2-related volumes of ethanol. Developing unit train destinations is a time-

consuming process, usually taking 3 to 5 years. The industry has responded to this challenge by

developing rail-to-truck transloading facilities for smaller-than-unit train shipments of ethanol.

X. CONCLUSIONS

This report was intended to start compiling real world data that would indicate the size and scope

of the investments necessary to achieve 36 billion gallons of renewable biofuels by 2022. What

USDA has shown in this report is:

(1) A rapid build-up in production capabilities is needed to meet the RFS2 targets for cellulosic

biofuels.

(2) The scope of the monetary investment for biorefineries is substantial.

(3) It is important to consider both sides of the market – the production/supply side and

mandate/consumption side – and how they respond to the RFS2 mandate.

(4) There are current infrastructure needs, in the form of blender pumps and rail and trucking

infrastructure which are in varying stages of being addressed by the market, though a careful

assessment of barriers to their development is needed.

(5) The U.S. farm sector is capable of producing a diverse complement of feedstocks to make the

biofuels industry a truly national effort.

(6) In addition, a process for identifying bottlenecks and barriers related to locating biorefineries

involving the federal government, Congress, states, the industry and interested stakeholders

can help facilitate a biorefinery system that is national in scope.

USDA intends this report to provoke discussions and looks forward to further work on this issue

which may prove to be one of the most important of the 21st century.

Contributors to this Report:

Sarah Bittleman OSEC

Meg Bolin RD

Bill Hagy RD

Velma Charles-Shannon ASCR

Renee Schwartz FAS

Jeffrey Steiner OCS

Tony Crooks RD

Bill Smith RD

Todd Atkinson FSA

Lynn Tjeerdsma FSA

Chavonda Jacobs-Young OCS

Ross Braun NRCS

Marilyn Buford FS R&D

Karen Larsen RD/RUS

Chris Nelson OBPA

Paul Trupo FAS

Harry Baumes OCE/OEPNU

Marina Denicoff AMS

Quinton Robinson OSDBV

Todd Campbell RD

19

USDA Biofuels Strategic Production Report

June 23, 2010

APPENDIX A.

Current Status of Biofuel Production in the United States

A. Ethanol

Currently, ethanol, from corn grain, and biodiesel, from soybean oil, animal fats, or restaurant

greases, are the only biofuels produced in the United States on a commercial scale. In the US,

there are currently 201 ethanol and 168 biodiesel facilities in production. The majority of this

biorefineries are located in the Central Eastern region of the country, comprised of Iowa,

Nebraska, Illinois, Minnesota, South Dakota, Indiana, and Ohio. Corn starch ethanol is not

considered an advanced biofuel for the purposes of the RFS2 standards and can contribute a

maximum of 15 billion gallons to the RFS2 targets.

Based on regional agronomic conditions, the Central Eastern region of the United States bears

the greatest potential for expansion in addition to the current production, followed in order by the

Southeast, Northwest, Northeast, and West, with the West projected to contribute less than 1% of

the goal of 21 billion gallons of advanced biofuel by 2022.